Is School Education at Risk? Fostering Unique Learning in the Digital AI Age by Hamad Yahya

Is School Education at Risk? Fostering Unique Learning in the Digital AI Age

by Hamad Yahya

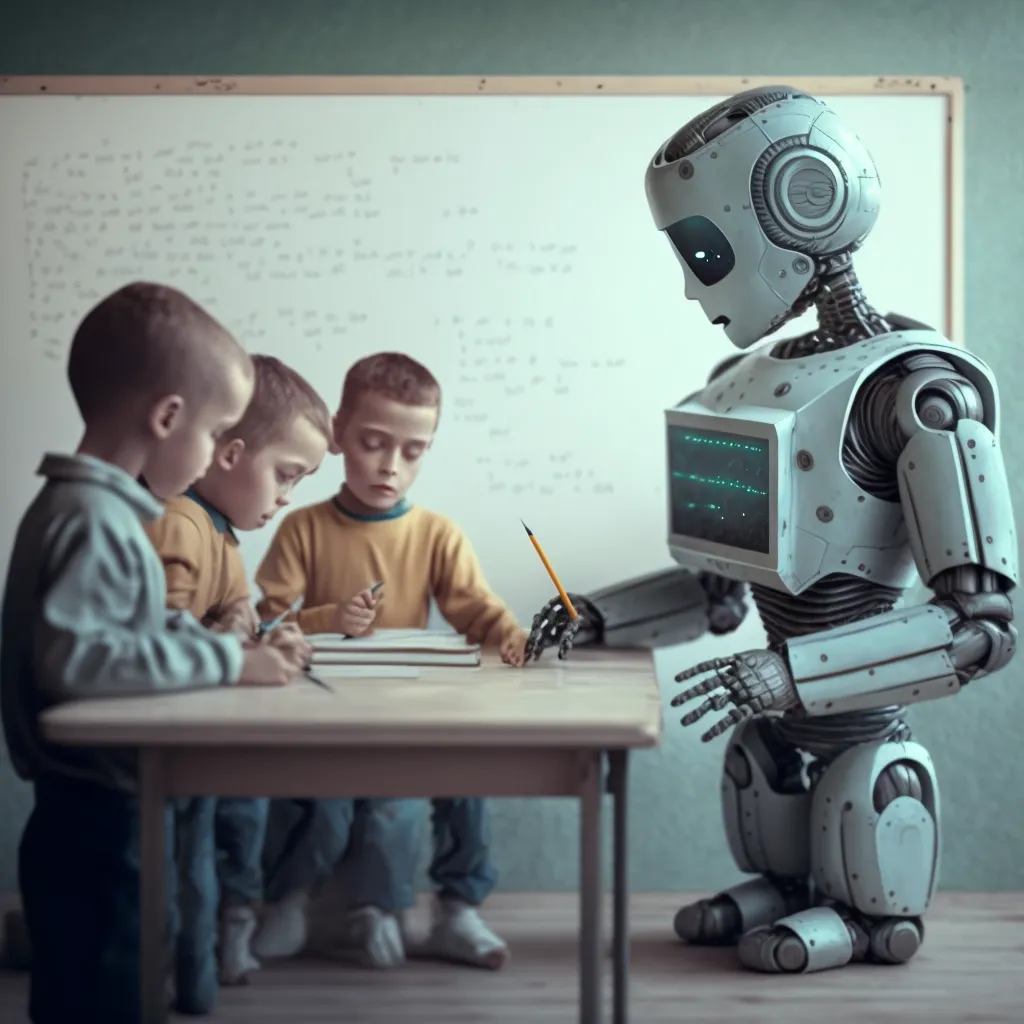

The transformative convergence of technology and education reshapes the learning landscape. The trends of artificial intelligence (AI) have accelerated this transformation, offering both opportunities and challenges. While AI holds the potential to revolutionize instruction (OECD, 2019), concerns about its impact on human interaction and the role of educators persist. This study examines the interplay between technology and human-centered education, exploring the limitations of online learning, the strengths of traditional approaches, and strategies for effectively integrating technology into educational practices. By investigating these areas, this article aims to contribute to the ongoing discourse on the future of education.

While traditional education prioritizes teaching over learning, the same approach continues to persist despite calls for change (Kohn, 1993). This approach often overlooks the significance of psychological principles in enhancing learning outcomes (Ryan & Deci, 2000). As technology advances, a notable gap emerges between digital-native learners and conventional teaching methods (Prensky, 2001). Resistance to change within educational institutions, often rooted in fear and resource constraints, slows the progress of educational development (Cuban, 1984; Hargreaves & Fullan, 2012). This resistance hinders the adoption of student-centered practices and positive motivation strategies, perpetuating reliance on extrinsic rewards (Pink, 2009).

While online learning uses new technology and offers flexibility, it presents its own set of challenges. For example, reduced social interaction, technical difficulties, and maintaining student motivation are common issues (Tufekci, 2014; Bonk & Dennen, 2009). Concerns about providing personalized feedback and addressing student isolation further underscore the limitations of online education (Picciano, 2002; Mizani et al., 2022). These challenges highlight the critical importance of human interaction in the educational process. Meanwhile, human-centered education prioritizes interaction and connection between the educator and learner, offering benefits that extend beyond mere content delivery. Teachers, acting as facilitators, provide personalized support and foster student engagement (Darling-Hammond, 2000). Collaborative learning and social-emotional development thrive in this environment (Vygotsky, 1978). By emphasizing active learning and critical thinking, human-centered education equips students with the skills necessary for complex problem-solving (Dewey, 1938). While technology serves as a valuable tool, it should complement, rather than replace, human interaction (Cuban, 1993).

To fully realize the potential of technology while preserving the essence of human-centered education, schools must adopt a strategic approach. Equipping educators with essential digital literacy and pedagogical skills through ongoing professional development is paramount (Cuban, 1984). Ensuring equitable access to technology for all students is crucial to bridging the digital divide (Selwyn, 2016). Leveraging technology to personalize learning experiences, informed by educational psychology, can cater to the diverse needs and abilities of individual students (Cheung et al., 2023). Fostering digital citizenship and media literacy, while considering the psychological impacts of technology use, is vital for students' overall well-being (Ribble, 2013; Lievens et al., 2018). Maintaining a balance between technology and human interaction remains essential (Darling-Hammond, 2000). By prioritizing student agency, collaboration, and critical thinking, schools can create dynamic and inclusive learning environments.

The convergence of technology and education presents both challenges and opportunities. While online learning offers flexibility, its limitations in fostering social interaction, personalized feedback, and student motivation underscore the enduring value of human-centered approaches. To thrive, education must strike a balance between technology and human-centered strategies. By prioritizing teacher-student interaction, collaborative learning, personalized instruction, and focusing on how learners will learn, schools can create engaging and effective environments that prepare students for the future. This balanced approach ensures that schools not only survive but thrive in the digital age, preserving the indispensable role of human connection in the learning process.

References

Bonk, C. J., & Dennen, V. (2003). Frameworks for research, design, benchmarks, training, and pedagogy in web-based distance education. Handbook of distance education, 331-348.

Cheung, S., Wang, F., Kwok, L., & Poulová, P. (Eds.). (2023). Personalized learning: Approaches, methods and practices.

Cuban, L. (1984). How Teachers Taught: Constancy and Change in American Classrooms, 1890-1980. Research on Teaching Monograph Series. Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED383498.pdf

Darling-Hammond, L. (2000). Teacher quality and student achievement. Education Policy Analysis Archives, 8. doi:10.14507/epaa.v8n1.2000

Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. Kappa Delta Pi.

Hargreaves, A., & Fullan, M. (2015). Professional capital: Transforming teaching in every school. Teachers College Press.

Kohn, A. (1993). Choices for Children: Why and How to Let Students Decide. Phi Delta Kappan, 75.(1), 8-20. Retrieved from https://www.alfiekohn.org/article/choices-children/

Lievens, E., Livingstone, S., McLaughlin, S., O'Neill, B., & Verdoodt, V. (2018). Children's rights and digital technologies. In International handbook of children's rights studies (pp. 1-27). Springer. doi:10.1007/978-981-10-3182-3_16-1

Mizani, H., Cahyadi, A., Hendryadi, H., Salamah, S., & Retno Sari, S. (2022). Loneliness, student engagement, and academic achievement during emergency remote teaching during COVID-19: The role of the God locus of control. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 9(1), 305. doi:10.1057/s41599-022-01328-9

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). (2021). OECD Digital Education Outlook 2021: Pushing the frontiers with artificial intelligence, blockchain and robots. doi:10.1787/589b283f-en

Picciano, A. (2002). Beyond student perceptions: Issues of interaction, presence, and performance in an online course. JALN, 6. doi:10.24059/olj.v6i1.1870

Pink, D. H. (2009). Drive: The surprising truth about what motivates us. Riverhead Books.

Prensky, M. (2001). Digital natives, digital immigrants. On the Horizon, 9(5), 1-6. Retrieved from https://www.marcprensky.com/writing/Prensky%20-%20Digital%20Natives,%20Digital%20Immigrants%20-%20Part1.pdf

Ribble, M. (2015). Digital citizenship in schools: Nine elements all students should know. International Society for technology in Education.

Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

Selwyn, N. (2016). Is technology good for education? Polity Press.

Tufekci, Z. (2017). Twitter and tear gas: The power and fragility of networked protest. Yale University Press. doi:10.25969/mediarep/14848

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in Society: Development of Higher Psychological Processes (M. Cole, V. Jolm-Steiner, S. Scribner, & E. Souberman, Eds.). Harvard University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctvjf9vz4

Comments

Post a Comment